Everybody nowadays says they develop software with agility: individuals and interactions, working software, customer collaboration, responding to change. Who wouldn’t agree, but the real complexity is in practice, when the principles are constantly challenged.

With over a year’s experience of running the six-week squads at Adbrain, I wanted to share what I’d learned.

How Agile masks micro-management

Business loves control, it’s in its nature: revenue forecasts, cost-benefit analyses, delivery deadlines — music to managers’ ears. But engineers are creatives and love freedom: prototype, design patterns, refactoring — ‘just one more week and it’s done’, — so how can it work?

The agile movement has been instrumental in finding a better balance in this tug of war and has proven to be effective in the last 15 years of mainstream adoption; software gets delivered faster, developers are happier and ultimately, innovation has accelerated. But with methodologies maturing, there’s the tendency to focus more and more on the processes rather than the principles. How do you get better at estimating task-for-user stories? What’s the best use case for TDD and BDD? So on and so forth.

Scrum has been refined to increase predictability, for example with a burn-down chart you can better understand the pace of delivery. This works very well if you build similar software, but can radical innovation be predictable?

Kanban has the advantage of keeping the focus and reducing wasted work and time. But the big picture is often lost and the awareness of the impact is diluted. It’s like walking in a colorful medieval village; you can see the pretty houses, colorful flowers and you get to know very well how to orientate in the maze,but only if you climb the adjacent hill can you appreciate how magnificent it is.

Sometimes I get the impression that developers are trapped in a cargo cult, being introduced to the rituals of agile that will bring the chimera of ‘freedom and power to engineers’, without realising that methodologies can become a smart trick for a more sophisticated, invasive micro-management tool.

Is playing planning poker the most interesting way to contribute? Don’t you, as a developer, aspire to have a more meaningful impact than a two-week sprint plan?

There’s a way to empower autonomy within a team without board members logging in to check lines of code: a neo-agile approach.

Mission, time-boxing, and responsibility

The key to staying away from micromanagement is to be outcome-driven, explicit about the resources and constraints and trust your team to get the job done.

The core of the system is a structure that exists between the business and the delivery team — the ‘squad’ — an autonomous cross-functional team that has six weeks to achieve a mission. It seems what everybody is doing, or at least saying is doing. But we’ve found a combination of characteristics that make it game-changing: mission, time-boxing, and responsibility.

I consider these six-week squads to be a fork of the Spotify squads, reinvented for a smaller, faster scale, and for a resource-constrained environment.

Mission: be specific, but give problems, not solutions

The mission is one of three cornerstones of the ‘squad’s’ success. It targets the specific area for improvement, crystallising the problem that needs to be solved. But it doesn’t provide a solution to implement; it’s the responsibility of the team to figure out how to do it.

An effective mission is results-oriented, it indicates the picture of success when the mission is achieved. It needs to be realistic and achievable in the six-week opportunity. It also needs to be narrow enough to guarantee focus, while being general enough to stay away from the details.

For example, if your problem is a product that is getting traction but requires a lot of engineers operations, you could be tempted to give a solution-based mission: ‘Add a management and monitoring UI for the product XYZ’. You could instead have an outcome-driven mission: ‘Streamline the XYZ process to allow the client service team to independently service our customers, in a reliable and automated way.’ This clearly states what the problem is and allows the squad members to figure out the best way to solve it, in six weeks. Together with the product owner, the team will work out what the best trade-off is to achieve the mission; instead of a UI they might build a command line tool for your geeky CS team. You’ll be surprised by their solution — it could be one you didn’t even think about!

By doing this, you create a double-sided effect. First the business has enough visibility to see how engineering work is contributing to its success, relaxing the control-freak instinct that often stems from from the lack of understanding on what the team is focusing on. On the other side, engineers have clarity regarding the business objective(s) to be achieved and the autonomy to implement the best solution without story points or other violently transparent tools.

The mission becomes a promise to solve problems, not build features. A ubiquitous language that everybody can understand and relate to.

Time-boxing, longer and actual

We all know from the project management triangle that you can fix only two out the three attributes: resources, time, and scope. But what the triangle is not telling us is an effective combination of the three: how many people work well together? What is a good duration of time to empower people? How precise do you want to be with the requirements?

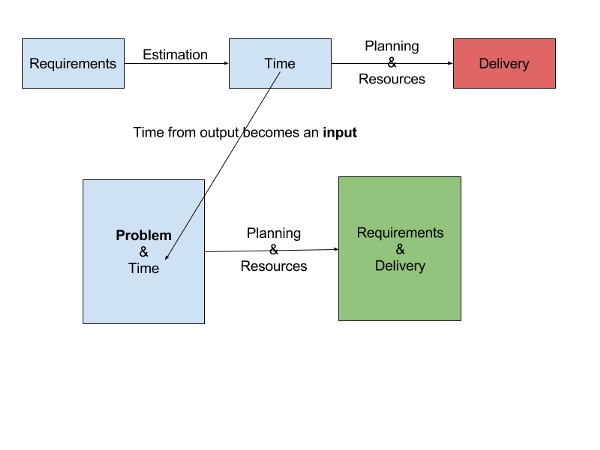

Regardless of the methodology you’re using, the real world works like this most of the time: you start with a set of detailed requirements of things to build, you put a non-trivial effort into estimating the effort and then you plan the resources needed to deliver on time. And you constantly fail to deliver.

We introduced what I call an ‘inversion of control’. Instead of forecasting the time based on estimation, you have time as a fixed element. You replace requirements with higher level problems to solve, and detailed estimations with order-of-magnitude complexity assessment. Then you let the team both define the requirements and build them!

There are also two other elements that make the system works well: longer duration and isolation from disruptions.

We settled on six weeks because it’s a duration that allows out-of-the-box thinking, prototyping and delivering a solution to non-trivial problems. It’s also long enough to allow for internal iterations but short enough to not create the illusion that the end is too far away.

You also want to protect the squads from disruptions and context-switching. There is a special squad that works on a weekly rotation, called ‘Solutions’, which is the first line of defence; among other responsibilities, it deals with production bug fixes and any urgent customer-facing needs. This ensures that the time spent in the six-week squads is predictable and usually free from disruptions, while the ‘Solutions’ team guarantees a first-class service to your customers.

You ultimately change the attitude from ‘We need these functionalities asap; how long will it take? Implement them until they are ‘really’ finished’ to ’We have this problem, you have six weeks’ opportunity to get the best trade-off delivered, go and do it!’. It protects against scope creep and problems of defining ‘done’ that come with agile.

Responsibility: Don’t finish tasks, achieve a mission

When a team controls both the scope and the execution, they are empowered to succeed and are the master of their own destiny. This is the key that makes people accountable to each other and fosters a collaborative environment.

Let’s assume your software delivery metrics are based on how many tickets you work on and how fast you open/close tickets. If somebody in your team needs help, even though you could assist, you might actually decide not to, as you’re focused on finishing your own task. But with squads nobody is measured on such metrics, their success is considered as a whole. You might then want to help others finish their work, because it’ll help you achieve the mission.

This will also prevent the go-it-alone cowboy behaviour:’ I’ll save the world by myself’. An interdependent autonomy emerges, you succeed when everybody else succeed, and everybody else will succeed when you can work autonomously to help the team. This emphasises the importance of the individual because it prevents Agile turning individual developers into cogs of the machinery (again), making the disposable clones within a more or less anonymous process.

You want to respect and leverage the seniority of the tech leads, as the order-of-magnitude complexity assessment can be done effectively only by those who have seen the long-term impact of their decisions multiple times — developing the necessary intuition to protect the team from taking shortcuts that they’ll soon regret.

As has been said before: ‘With great power comes great responsibility’. The good news is that smart, empowered people can be trusted.

Not just bells and whistles

Refining this neo-agile methodology for over a year has allowed us to also discover the downsides of it.

The mission was very helpful in determining the ‘what’, but was lacking in terms of providing more context on ‘why’ the mission is important and how it affects the company success. The product owners made huge efforts to ensure that in the kick-off meeting — and throughout the whole duration of the squad — there was as much clarity regarding the latter as there was on the former. I firmly believe that context and knowledge sharing are therefore key to empowering a team.

We also observed a tendency to release everything at the end in a waterfall approach. It sounds counterintuitive, but missions are quite ambitious and empowered people want to succeed! There’s an instinct to squeeze in as much scope as possible with the illusion that ‘we can do it’. Instead of imposing a cadence in the internal release (e.g. sprints), we asked the team to agree on an MVP (Minimum Viable Product) at the beginning of the six weeks — which represented something that should be by the halfway point.

Even if the six-week squads are game-changing in terms of empowerment, they could be perceived as a myopic tool: they can be attributed to short-sighted planning and trade-offs in both commercial requests and tech decisions. But be very careful of falling into the trap of blaming the tool; squads are six-week opportunities to make progress on business objectives that contribute to the success of the company. If you struggle with breaking down a bigger problem into smaller, achievable milestones or you don’t give enough clarity on the longer term vision, it’s mainly a problem of planning and lack of context.

By way of example at one point we needed a significant increase in efficiency in an area of the stack. We recognised it was a major effort — and would have been a miracle if a team of four people solved the problem in six weeks — but we accepted the risk and went ahead anyway. At the end, a ‘follow-up’ squad was needed for the same problem. Was this first squad a failure? Definitely not; it was a planning error. We didn’t respect one of the core roles — the mission had to be realistic and achievable — and we failed at breaking the problem down further.

There is also plenty of room to improve on involving everyone in understanding and having a say in every stage of the planning and roadmapping; providing a bottom-up approach for initiatives to be prioritised.

A ubiquitous system

Six-week squads allow you to shift from delivering a laundry list of things — call it user stories, requirements, features etc. — to solving higher level problems that everybody in the company can understand and relate to. It can be a customer problem, an engineering challenge, a cost optimisation effort; everybody will understand what the tech team is working on and how it contributes to the company success.

Prioritisation is a trade-off exercise, which is mostly hidden and leaves the business under the illusion that everything will get delivered, at some point. This triggers the control-freak instinct when the ticking clock breaks the bubble.

With squads, the trade-offs are exposed organically from the very beginning. There’s no need to micromanage because you only talk about realistic work that gets achieved.

There are well-known examples in the industry of successful innovative Agile methodologies, like Spotify or Transferwise,but they are only effective in large teams and later-stage products.

Six-week squads work on smaller scale (12–20 people) and in the context of greater need for adaptability. You can manage to innovate quickly, delivering values to your customers but your mustn’t forget to have strong foundations for growth without micromanaging.

***

Don’t forget about our forthcoming CTO Craft Con 2021: The Delivery One on 23 – 25 March where we’ll be hosting some incredible speakers. Find out more and get your tickets here!

If you or your CTO / technology lead would benefit from any of the services offered by the CTO Craft community, use the Contact Us button at the top or email us here and we’ll be in touch!

Subscribe to Tech Manager Weekly for a free weekly dose of tech culture, hiring, development, process and more.